Sponsored post by 1919 Investment Counsel

Nearly as old as humanity itself, agriculture has become a global industry replete with numerous challenges and opportunities. Our twenty-first century industrialized agricultural models and infrastructure are tasked with feeding a huge global population - no small feat. However, concerns over the industry’s ability to sustain food production in an efficient manner have existed for years. Environmental concerns sit atop many investors’ lists of grievances with large livestock or agricultural companies. Consumer demand for sustainable products is growing, as evidenced by increasing desire for plant-based proteins and demand for better treatment of livestock protein animals.

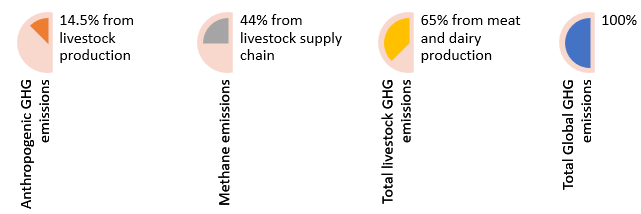

Environmental concerns with the enormous livestock industry are many, and well-founded; livestock production contributes 14.5% of all anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. [1] Not only is this contribution higher than the entire transport sector, but the five largest meat and dairy producing companies emit more than Exxon, BP, or Royal Dutch Shell combined. [2] Agricultural production results in two types of emissions: mechanical, caused by equipment and machinery operated on farmland; and non-mechanical, caused by biological processes such as  enteric fermentation and manure management. [3] Non-mechanical emissions are significantly higher than mechanical emissions; beef and dairy production cause the highest enteric emissions of animal-based agriculture, contributing 65% of the livestock sector’s total GHG emissions, and livestock supply chains are responsible for 44% of methane emissions. Livestock GHG emissions are just one challenge; deforestation is another. Early campaigns to combat climate change sought to halt deforestation, because it creates new emissions through increased farmland and cropland, and also reduces carbon absorption as the number of trees dwindles. No matter which challenge is being addressed, the agricultural industry lacks adequate, standardized, and verified reporting on emissions and environmental impact, improvements which could help companies understand their own environmental footprints, and implement efficiencies. [4]

enteric fermentation and manure management. [3] Non-mechanical emissions are significantly higher than mechanical emissions; beef and dairy production cause the highest enteric emissions of animal-based agriculture, contributing 65% of the livestock sector’s total GHG emissions, and livestock supply chains are responsible for 44% of methane emissions. Livestock GHG emissions are just one challenge; deforestation is another. Early campaigns to combat climate change sought to halt deforestation, because it creates new emissions through increased farmland and cropland, and also reduces carbon absorption as the number of trees dwindles. No matter which challenge is being addressed, the agricultural industry lacks adequate, standardized, and verified reporting on emissions and environmental impact, improvements which could help companies understand their own environmental footprints, and implement efficiencies. [4]

GHG emissions from the agricultural sector create a negative feedback loop; livestock companies face increasing problems and costs from extreme weather events, caused by climate change, which is exacerbated by GHG emissions. In recent years, developing economies have faced $96 billion in damaged or lost crop and livestock production as a result of extreme weather events. More developed economies face these problems, too: JBS, a major beef processing company, reported in 2017 that it had partially discontinued certain operations in Brazil because its water supply was lacking, due to climate change impacts. [5]

In addition to JBS, other global producers and processors in the livestock and agriculture sector include Tyson Foods, Sanderson Farms, JBS, Smithfield Foods, Cargill, Hormel Foods, Perdue Farms, ConAgra Foods, Pilgrim’s Pride, Oscar Mayer (a division of Kraft Heinz), and Sysco Corp. [6] Many of these companies are privately held, and would not be commonplace in an investment portfolio. Some activist investors have engaged with these meat and livestock companies, with mixed levels of success. At the companies that are publicly traded, shareholder resolutions have been filed on numerous environmental concerns, including water stewardship, GHG emission reduction programs, and deforestation prevention efforts. [7]

When reaching beyond farming companies, it is harder to avoid exposure to supply chain players, which deliver meat to consumers’ tables. The chain includes farm companies like Tyson Foods or Smithfield Farms, food distributors like Gordon Food Service or Sysco Corp., and retailers like Kroger; avoiding investment in both distributors and retailers eliminates nearly an entire sector. However, retail companies can engage with their suppliers – the farmers – to encourage committed action to be as sustainable and efficient as possible.

The corporate sector plays an enormous role in livestock’s negative environmental footprint, but consumers who lessen their reliance on animal-based proteins simultaneously decrease their own carbon footprints. If nothing changes – neither on the producer nor consumer sides – agricultural emissions will be the entire world’s carbon budget by 2050, with livestock as the primary contributor. [8] There are multiple reasons for consumers to decrease their livestock consumption. Livestock products are often an inefficient source of nutrition: chicken, the most efficient animal protein sector, converts only about 11% of gross feed energy into animal protein. [9] A shift in diets in those countries’ where meat is favored, toward more plant-based foods, could meaningfully reduce emissions, as countries that consume the most meat products also pollute the most: Argentina, New Zealand, and the U.S. top the list. [10]

If U.S. consumers substituted beef with plant-based protein from beans, the country could achieve 46% or more of its 2020 GHG emissions targets. [11]

Demand for alternatives to meat-based proteins is rising and food technology innovations have made it easier to create plant-based protein products that consumers want to eat. The three main techniques are advanced plant products, fermentation-created meat, and cell culture-created proteins. [12] These innovations and an increased use of plants helps eliminate the problems of traditional meat production. Venture capitalists are eager to invest in new plant-based protein innovators, and there are many market opportunities for alternative proteins. Annual global sales of plant-based meat alternatives have grown on average 8% each year from 2010 to 2018, and industry estimates project the sector to expand globally at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8.29% from 2017 to 2021. Finally, U.S. retail sales alone of plant-based foods that directly replace animal products grew 8.1% in the 12 months preceding August 2017. [13]

Market and investment opportunities are only some of the benefits to reducing reliance on animal-based proteins; environmental efficiencies and improvements abound. Global food chains producing both plant and animal products generate a large amount of food waste. Multiple organizations around the world have suggested using surplus food and food waste products (no longer fit for human consumption) as feed products for pigs, a major livestock commodity. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) recommends that by-products or food waste that humans cannot eat should be fed to livestock, following the positive example used in Japan. In Japan, 52% of waste from the food industry is used as livestock feed, which reduces food waste and lessens the environmental impact of livestock farming as crops are not grown just as feed. Benefits also result from pigs themselves (as among the most efficient convertors of food waste), and from less rainforest destruction (South American soy fields are a major supplier of livestock feed). [14]

The food-waste-as-feed model also significantly lowers livestock companies’ costs. In October 2017, livestock feed costs in the U.K. were 62% of the total production costs. Conversely, in Japan, industrial food-to-feed recycling plants can deliver surplus food-based feed at half the cost of conventional feed. Of course, serious regulations must be followed to use surplus food and food waste as feed systems; the process is very successful, but all scraps or surplus must be boiled or heat-treated to specifications to become safe feed products and to avoid major disease outbreak. [15]

Protecting rainforests and reducing cropland acreage are just two components of more sustainable protein production. There are other, less obvious ways to reduce emissions while producing animal-based protein. For example, a collaborative project in Bern, Switzerland is studying how to reduce emissions produced by dairy cows: one suggestion is to allow dairy cows to live two years longer than they are currently kept. Young dairy cows produce more methane and less milk; prolonging the lives of existing cows – rather than constant cow turnover – could lower the herd’s overall methane emissions while providing a higher quantity of milk. This simple step would save 5% of methane emissions per kilo of milk. The study also aims to better quantify the resources consumed in raising dairy cows; methane is produced during digestion, so understanding cows’ feed consumption, and perhaps limiting those resources, may result in lower methane emissions and thus lower GHG emissions.[16]

Negative environmental impacts from industrial livestock production have real consequences for climate change, and the grand scale of industrial agriculture is a significant force to address. Concerned investors may avoid investing in the livestock companies themselves, which also helps improve the investor’s portfolio carbon footprint. Another step is to encourage companies to adopt sustainable agriculture practices through corporate engagement. Additionally, investors can support retailers that uphold sustainable agriculture and offer many options for non-animal-based protein products. On a large scale, it is a difficult objective for investors to starve livestock companies of capital, as government regulatory support and financial companies’ loans to industrial farms is not easily swayed. Further, there are likely to be numerous financial lenders to farming companies, with few lending policies that address sustainable agriculture; asking these lenders to cease lending to farm companies is unlikely to succeed, because farms and livestock companies comprise such a small portion of the financier’s loan portfolio. Ending capital flows to livestock companies, or divesting from all food retailers is a difficult objective. However, investors can achieve their own environmental and agricultural goals by easily avoiding the main animal-based protein producers and processors.

Negative environmental impacts from industrial livestock production have real consequences for climate change, and the grand scale of industrial agriculture is a significant force to address. Concerned investors may avoid investing in the livestock companies themselves, which also helps improve the investor’s portfolio carbon footprint. Another step is to encourage companies to adopt sustainable agriculture practices through corporate engagement. Additionally, investors can support retailers that uphold sustainable agriculture and offer many options for non-animal-based protein products. On a large scale, it is a difficult objective for investors to starve livestock companies of capital, as government regulatory support and financial companies’ loans to industrial farms is not easily swayed. Further, there are likely to be numerous financial lenders to farming companies, with few lending policies that address sustainable agriculture; asking these lenders to cease lending to farm companies is unlikely to succeed, because farms and livestock companies comprise such a small portion of the financier’s loan portfolio. Ending capital flows to livestock companies, or divesting from all food retailers is a difficult objective. However, investors can achieve their own environmental and agricultural goals by easily avoiding the main animal-based protein producers and processors.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Coller FAIRR, Protein Producer Index Report Summary Version

[2] Novethic, Les cinq plus gros producteurs de viande et de lait polluent plus que les petroliers, 2018

[3] Coller FAIRR, Protein Producer Index Report Summary Version

[4] Coller FAIRR, Protein Producer Index Report Summary Version

[5] Coller FAIRR, Protein Producer Index Report Summary Version

[6] The National Provisioner, 2018

[7] Ceres

[8] Coller FAIRR, Plant-Based Profits, 2018

[9] Coller FAIRR, Plant-Based Profits, 2018

[10] Novethic, Les cinq plus gros producteurs de viande et de lait polluent plus que les pétroliers, 2018

[11] Coller FAIRR, Plant-Based Profits, 2018

[12] Coller FAIRR, Plant-Based Profits, 2018

[13] Coller FAIRR, Plant-Based Profits, 2018

[14] Feedback, Feeding Surplus Food to Pigs Safely, 2018

[15] Feedback, Feeding Surplus Food to Pigs Safely, 2018

[16] Agence Télégraphique Suisse, Réduire de 20% les gaz à effet de serre produits par les vaches, 2018