By Sidney R. Hargro

From the disproportionate impact and deaths of Black Americans due to COVID-19 pandemic (1) to the recent senseless murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, the latest of an untold number of deaths at the hands of white police (2) and citizen vigilantes, four centuries of traumatic white supremacist culture in the lives Black men, women, and families are once again exposed to the world. These cases are not simply due to “a few bad actors,” but rather a pervasive culture of white supremacy and a worldview that produced policies, practices, and institutions that normalize anti-black behavior and make it socially acceptable to harass, assault, or even murder Black bodies. The system, therefore, is not broken. It was designed to function this way and will continue to do so until we dismantle it.

We are now experiencing a level of civil unrest in cities across the country that is reminiscent of the week following the assassination of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968 when a wave of protests and riots swept the United States. Also similar to the protests of 1968, we are witnessing a violent response by police and National Guard against protestors, firing tear gas canisters and rubber bullets, and using high pressure pepper spray to intimidate and disperse those advocating for change.

This is America and Philanthropy Operates in It

This is America in 2020. This is the America that Black and Indigenous people and other people of color have experienced for generations. This is the America my grandfather and my father warned me about. This is the America that I discuss with my children and now the one they discuss on their Instagram stories. It is an America that has been normalized through hate, a lack of information, a lack of understanding, and silence. White privilege, fear, and fragility have sustained a culture of supremacy at the cost of Black lives and livelihoods. This America is one that philanthropy must confront with vigorous focus, intentionality, accountability, and resources.

In recent years, foundations across the country have slowly become comfortable with naming and discussing equity as a critical catalyst for social change. Aided by Black leadership in major foundations, a lens has been offered which seeks to change traditional philanthropic paradigms. Darren Walker, from The Ford Foundation, called for philanthropy to move from a charity mindset to one that seeks justice in his book From Generosity to Justice: A New Gospel of Wealth. (3)

In Philadelphia, Philanthropy Network created the Equity in Philanthropy Initiative, designed to support, challenge, and advise funders as they seek to center equity in their work. The signature component of the initiative was a year-long Equity in Philanthropy Cohort which included programming, peer-to-peer support, and customized assistance for the leaders and board members of 12 funders in the region. Cohort members were among the funders leading the charge at the start of the COVID-19 crisis, offering 10 to 20 percent of their endowment for flexible support of nonprofit and even as their endowments decreased in a volatile stock market. These funders moved swiftly from a verbal commitment to equity to action, choosing humanity over assets and were intentional about naming and supporting organizations led by people of color, immigrants, refugees, and undocumented residents of Greater Philadelphia. But, this is merely a start of a full commitment to equity. Far more work is needed to address the root causes of the pain and trauma Black people are experiencing.

A Call for a New Endgame: Liberation

Many will agree that the philanthropic sector has a propensity to fund research and create new frameworks and models for impact. However, these approaches have fallen short of addressing systems of racial injustice. What philanthropy needs is not a new framework, but a new endgame, racial liberation. The pursuit of racial liberation requires an intentional and laser-like focus on breaking systems of oppression that are based in white supremacist culture. This requires imagination, followed by the ability to see the same “promised land” that Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. saw from his metaphorical mountaintop, a land where Black people are free to run, walk, participate in birding, even be arrested if unlawful acts are committed, without excessive harassment and loss of life. It also means delivering access to essential services like public internet, an excellent educational experience, healthcare, and quality food choices, to name a few, regardless of where they live or the color of their skin.

Today, there is an urgent need for philanthropic institutions and philanthropists to take more deliberate and intentional steps to dismantle white supremacy in all its forms and embrace a new endgame of liberation. For initial steps, I am calling for three things: direct confrontation of white supremacist practices, a commitment to dismantling white supremacy, and prioritizing liberation as a philanthropic goal.

First, philanthropy must acknowledge the white supremacist worldviews at play in conventional grantmaking practices. There are very few actions that make up the “must dos” for foundation to be in compliance with the IRS or the founding documents. The rest is made up. For example, the definition of “risk.” How many times have foundation boards used the word "risk" as a rationale to not fund organizations led by Black people or small fiscally-sponsored organizations serving Black communities? Who gets to determine the bar for what is a risk and what is not? With predominantly White executive and board leadership,(4) many foundations operate with an unconscious bias which advantages white culture and disadvantages all other cultures and methods of operation. Additionally, foundations often establish policies and practices which support the bias. For example, foundations often engage in excessive due diligence such as requiring expensive financial audits and/or requiring a certain budget size before a nonprofit can apply. These operational practices miss the abundance of small grassroots organizations led by people of color who achieve great social impact in their communities but are unable to apply to well-known foundations due to (arbitrary) rules of grantmaking policy. The rubrics and approaches to hiring team members as well as recruiting and selecting board members continue to produce low levels of diversity, and little, if any, presence of Black team members. Boards are often filled with affluent professionals who have no knowledge about the lived experience of the communities they aim to serve. In some cases tokens of culture are in place, the designated representative who is expected to speak for the entire race or identity group. Foundation endowments, even in the age of socially responsible investing, often include alternative investments that are designed specifically for making the foundation money without regard to the negative impact on people. Finally, institutional meritocracy is pervasive in foundation operational practice, funding only the organizations that are deemed to have major capacity, usually White-led, who are able to creatively show their impact in reports and grant proposals. However, the meritocracy frame means the foundation defines what merit is acceptable and does not take into account many years of underinvestment in smaller, more grassroots organizations led by people of color. These are just a few examples of foundation practices which privilege white culture. Part of philanthropic change is to undertake a detailed assessment of how white supremacist culture is at play in grantmakkng practices. With ongoing feedback and reflection through trusted relationships with nonprofits and peers, philanthropy can expose additional practices that are held in place due to white supremacist culture and norms.

Second, philanthropy must explicitly commit to dismantling white supremacy.

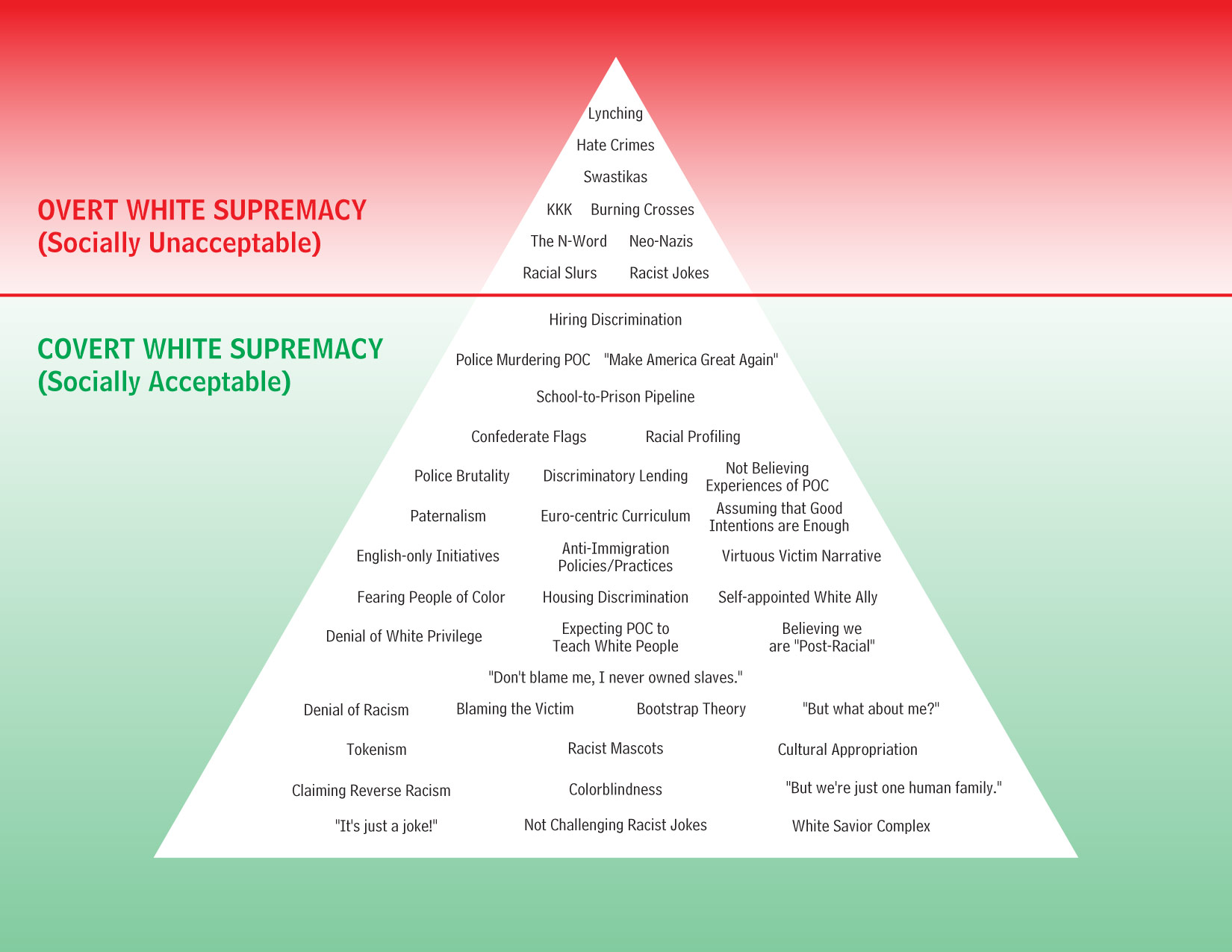

In August of 2017, a week after beginning my post as the leader of Philanthropy Network Greater Philadelphia, and before I had the chance to issue an official hello to the members of the Network, America experienced another crisis as the Charlottesville White Nationalist protests as they fought the removal of a Robert E. Lee statue and spewed slogans like, “Jews will not replace us.” I wrote a response titled, A Response to White Supremacy from the Birthplace of Freedom. Several philanthropy peers contacted me stating their surprise but approval of introducing the term “white supremacy” in highly visible philanthropic discourse in our region. I knew then it would be an uphill battle to engage in real talk and truth about white supremacy, though most foundations were warming to the idea of centering equity in their work. At the operational and governance level of most foundations, it is safe to say the term white supremacy is one that is not often used. I believe this is because the term conjures up images from scenes like Charlottesville, and of White Nationalists, hate groups, cross-burnings, swastikas, and the Ku Klux Klan, while foundation team members and boards for the most part believe they are “good people” and that they are behaving in ways that serve the greater good. Or, maybe it’s their belief that funding programs and supporting neighborhoods that are predominately Black renders them immune to white supremacy. It could also be because they have friends or team members who are Black, a sure sign that they are “color blind.” In order to publicly establish a commitment to dismantling white supremacy, we must become keenly aware of the overt, highly visible, and socially unacceptable forms of white supremacy as well as the subtle, more covert and socially acceptable forms of white supremacy. Many, myself included, believe that the covert, socially acceptable forms of white supremacy are responsible for holding the entire system of anti-black ideas, policies, practices and institutions in place. Therefore, to address it, we must engage in an ongoing examination of it along with an explicit public commitment to dismantling it during the current generation.

(Credit: Safehouse Progressive Alliance for Nonviolence and adapted by Ellen Tuzzolo)

Third, philanthropy must definitively establish liberation as the new endgame. The start of a new decade often coincides with the development of new strategic plans or at the very least what is known as a “strategic refresh.” A strategic plan presents the key priorities, objectives, and work of the foundation over the next 3-5-10 years. Therefore, decisions that are made have a direct and deep impact on nonprofits for a long period of time. Liberation philanthropy begins with a strategic focus and commitment to explicitly address the end to racial injustice that is not time-bound. It requires an analysis of systemic root causes, followed by the active elimination of the normalized ideas, policies, and practices that are anti-black. In other words, philanthropy must actively become what, Ibram X. Kendi defines as an anti-racist.(5) Ibram argues that the opposite of “being a racist” is not “not being a racist.” The opposite of “being a racist” or one who advances white supremacist culture and worldviews is being “anti-racist.” In liberation philanthropy, it is not about who you are but the actions you take to dismantle white supremacist ideas, policies, practices and hold your institution accountable to change.

Engaging in liberation philanthropy at minimum includes:

- Reviewing grantmaking practices to center flexible support for organizations of all sizes that are led by Black, Indigenous and People of Color;

- Supporting those organizations' capacity to communicate their story and attract future support;

- Including beneficiaries in strategic decision-making to assure that decisions are aligned with their lived experience;

- Appointing Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color at all levels staffing, leadership, and governance;

- Examining and revising internal processes for elements that are informed by a white supremacist worldview;

- Participating in collective, pooled efforts to support grassroots advocacy organizations that advance pro-Black and anti-racist policies; and

- Supporting local media organizations that offer a platform for community voices from communities of color to embrace their narrative for their community.

The new endgame of liberation will require a level of truth-telling and honesty that has been absent in the philanthropic sector, shying away from real discussions about race and intersectionality, power, and advocacy. It will require rigorous self-reflection and critique without defensiveness. Without this shift, philanthropy will continue to be palliative in nature, choosing to minimize pain without dealing with the root cause of the human condition for Black, Indigenous, and communities of color.

(1) Center for Disease Control and Prevention, COVID-19 in Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups

(2) Washington Post, Fatal Force, Police Shootings Database

(3) From Generosity to Justice: A New Gospel of Wealth, Darren Walker

(4) State of Diversity Nonprofit and Foundation Leadership, Battalia Winston

(5) Best-selling author, Ibram X. Kendi, on PBS

Sidney R. Hargro is president of Philanthropy Network Greater Philadelphia.

sidney@philanthropynetwork.org

@SidneyRHargro